(WIP) [译] DDIA Second Edition 第二章 - 定义非功能性需求

Chapter 2. Defining Nonfunctional Requirements

第二章 - 定义非功能性需求

The Internet was done so well that most people think of it as a natural resource like the Pacific Ocean, rather than something that was man-made. When was the last time a technology with a scale like that was so error-free?

— Alan Kay, in interview with Dr Dobb’s Journal (2012)

互联网的构建是如此成功,以至于大多数人将其视为像太平洋一样的自然资源,而非人造之物。上一次出现规模如此庞大且近乎零差错的技术是什么时候?

— Alan Kay 接受 Dr Dobb’s Journal 的采访(2012)1

If you are building an application, you will be driven by a list of requirements. At the top of your list is most likely the functionality that the application must offer: what screens and what buttons you need, and what each operation is supposed to do in order to fulfill the purpose of your software. These are your functional requirements.

如果你正在构建一个应用程序,你将被一系列的需求来驱动。在您的需求列表顶端,最有可能的是应用程序必须提供的功能:需要哪些屏幕和按钮,以及每个操作应实现何种功能以满足软件的目标。这些就是您的功能性需求。

In addition, you probably also have some nonfunctional requirements: for example, the app should be fast, reliable, secure, legally compliant, and easy to maintain. These requirements might not be explicitly written down, because they may seem somewhat obvious, but they are just as important as the app’s functionality: an app that is unbearably slow or unreliable might as well not exist.

此外,你可能还有一些非功能性需求:例如,应用程序应该快速、可靠、安全、符合法律规定(legally compliant)且易于维护。这些需求可能没有被明确地写下来,因为它们似乎有些显而易见,但它们与应用程序的功能同等重要:一个慢得无法忍受或不可靠的应用程序,几乎等同于不存在。

Many nonfunctional requirements, such as security, fall outside the scope of this book. But there are a few nonfunctional requirements that we will consider, and this chapter will help you articulate them for your own systems:

-

How to define and measure the performance of a system (see “Describing Performance”);

- What it means for a service to be reliable—namely, continuing to work correctly, even when things go wrong (see “Reliability and Fault Tolerance”);

- Allowing a system to be scalable by having efficient ways of adding computing capacity as the load on the system grows (see “Scalability”); and

- Making it easier to maintain a system in the long term (see “Maintainability”).

许多非功能性需求(例如安全性)不在本书讨论范围内。但我们会探讨其中几个关键的非功能性需求,本章将帮助你为自己的系统明确表述这些需求:

- 如何定义和衡量系统的性能(performance)(参见“描述性能”);

- 服务具备可靠性(reliable)的含义——即在出现故障时仍能持续正确运行(参见“可靠性与容错”);

- 能通过有效的方式在系统负载增长时增加计算能力(computing capacity),实现系统的可扩展性(scalability)(参见“可扩展性”);以及

- 使系统更易于长期维护(参见“可维护性”)。

The terminology introduced in this chapter will also be useful in the following chapters, when we go into the details of how data-intensive systems are implemented. However, abstract definitions can be quite dry; to make the ideas more concrete, we will start this chapter with a case study of how a social networking service might work, which will provide practical examples of performance and scalability.

本章介绍的术语在后续章节中也将非常有用,届时我们将深入探讨数据密集型系统的实现细节。不过抽象定义可能略显枯燥;为了让概念更具体,我们将以一个社交网络服务的运作为案例开始本章,这将为性能和可扩展性提供实际范例。

Case Study: Social Network Home Timelines

案例:社交媒体主页时间线

Imagine you are given the task of implementing a social network in the style of X (formerly Twitter), in which users can post messages and follow other users. This will be a huge simplification of how such a service actually works [1, 2, 3], but it will help illustrate some of the issues that arise in large-scale systems.

假设你的任务是实现一个类似X(前身为Twitter)的社交网络,用户可以在其中发布消息并关注其他用户。这将是对此类服务实际运作方式的极大简化[12, 23, 34],但有助于说明大规模系统中出现的一些问题。

Let’s assume that users make 500 million posts per day, or 5,800 posts per second on average. Occasionally, the rate can spike as high as 150,000 posts/second [4]. Let’s also assume that the average user follows 200 people and has 200 followers (although there is a very wide range: most people have only a handful of followers, and a few celebrities such as Barack Obama have over 100 million followers).

假设用户每天发布5亿条帖子,平均每秒发布5800条。偶尔发布速率会激增至每秒15万条5。同时假设平均每个用户关注200人,拥有200名关注者(尽管个体差异很大:大多数人只有少量关注者,而少数名人如巴拉克-奥巴马则拥有超过1亿关注者)。

Representing Users, Posts, and Follows

表示用户、发帖与关注关系

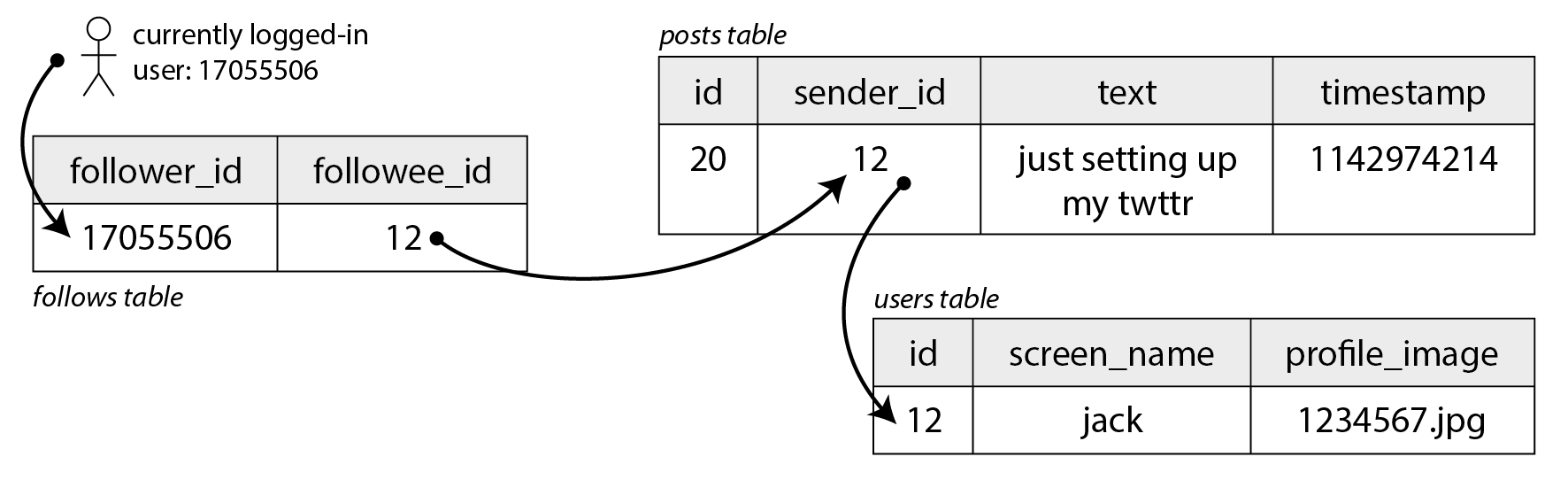

Imagine we keep all of the data in a relational database as shown in Figure 2-1. We have one table for users, one table for posts, and one table for follow relationships.

假设我们将所有数据保存在一个关系数据库中,如图2-1所示。我们用一个表存储用户信息,一个表存储发帖内容,另一个表存储关注关系。

图2-1:一个简单社交网络的关系型数据模型,支持用户间相互关注。

Let’s say the main read operation that our social network must support is the home timeline, which displays recent posts by people you are following (for simplicity we will ignore ads, suggested posts from people you are not following, and other extensions). We could write the following SQL query to get the home timeline for a particular user:

假设我们的社交网络必须支持的主要读操作是主页时间线——显示你关注的人最近发布的帖子(为简化起见,我们将忽略广告、未关注用户的推荐帖子及其他扩展功能)。我们可以编写以下SQL查询来获取特定用户的主页时间线:

SELECT posts.*, users.* FROM posts

JOIN follows ON posts.sender_id = follows.followee_id

JOIN users ON posts.sender_id = users.id

WHERE follows.follower_id = current_user

ORDER BY posts.timestamp DESC

LIMIT 1000

To execute this query, the database will use the follows table to find everybody who current_user is following, look up recent posts by those users, and sort them by timestamp to get the most recent 1,000 posts by any of the followed users.

为了执行这个查询,数据库将使用关注关系表(follows)查找当前用户关注的所有人,检索这些用户最近发布的帖子,并按时间戳排序以获取被关注用户最新发布的1000条帖子。

Posts are supposed to be timely, so let’s assume that after somebody makes a post, we want their followers to be able to see it within 5 seconds. One way of doing that would be for the user’s client to repeat the query above every 5 seconds while the user is online (this is known as polling). If we assume that 10 million users are online and logged in at the same time, that would mean running the query 2 million times per second. Even if you increase the polling interval, this is a lot.

帖子需要保持时效性,因此我们假设在用户发布内容后,其关注者应在5秒内看到该帖子。实现方式之一是让用户客户端在在线期间每5秒重复执行上述查询(这称为轮询,polling)。假设同时在线登录用户数为1000万,则意味着每秒需执行200万次查询。即使延长轮询间隔,这个数量依然非常庞大。

Moreover, the query above is quite expensive: if you are following 200 people, it needs to fetch a list of recent posts by each of those 200 people, and merge those lists. 2 million timeline queries per second then means that the database needs to look up the recent posts from some sender 400 million times per second—a huge number. And that is the average case. Some users follow tens of thousands of accounts; for them, this query is very expensive to execute, and difficult to make fast.

此外,上述查询的成本相当高:如果你关注了200人,数据库需要获取这200人中每个人最近发布的帖子列表,并合并这些列表。每秒200万次时间线查询,意味着数据库每秒需要查找发帖人近期发帖4亿次——这是一个巨大的数字。而这还只是平均情况。有些用户关注了数万个账号,对他们而言,执行该查询的成本极高且难以优化。

译注:由于数据库内部的查询机制,实际在物理层面上,查询每一个用户的 200 个关注人的发帖,不需要 200 次读取。这里做简单的乘法只是逻辑上的简化描述。真正想要理解数据库查询,需要看数据库方面的书籍。

Materializing and Updating Timelines

预构建(Materializing)与更新时间线

How can we do better? Firstly, instead of polling, it would be better if the server actively pushed new posts to any followers who are currently online. Secondly, we should precompute the results of the query above so that a user’s request for their home timeline can be served from a cache.

我们如何改进呢?首先,与其采用轮询(polling)方式,不如让服务器主动将新帖子推送(push)给所有在线的关注者。其次,我们应该预先计算(precompute)上述查询的结果,以便用户请求主页时间线时可以直接从缓存中获取。

Imagine that for each user we store a data structure containing their home timeline, i.e., the recent posts by people they are following. Every time a user makes a post, we look up all of their followers, and insert that post into the home timeline of each follower—like delivering a message to a mailbox. Now when a user logs in, we can simply give them this home timeline that we precomputed. Moreover, to receive a notification about any new posts on their timeline, the user’s client simply needs to subscribe to the stream of posts being added to their home timeline.

假设我们为每个用户存储一个包含其主页时间线的数据结构,即他们所关注用户近期发布的帖子。每当某个用户发布帖子时,我们查找该用户的所有关注者,并将这条帖子插入每位关注者的主页时间线——就像将信件投递到邮箱中。现在当用户登录时,我们只需将预先计算好的主页时间线提供给他们。此外,为了接收时间线上新帖子的通知,用户客户端只需订阅正在添加到其主页时间线的帖子流即可。

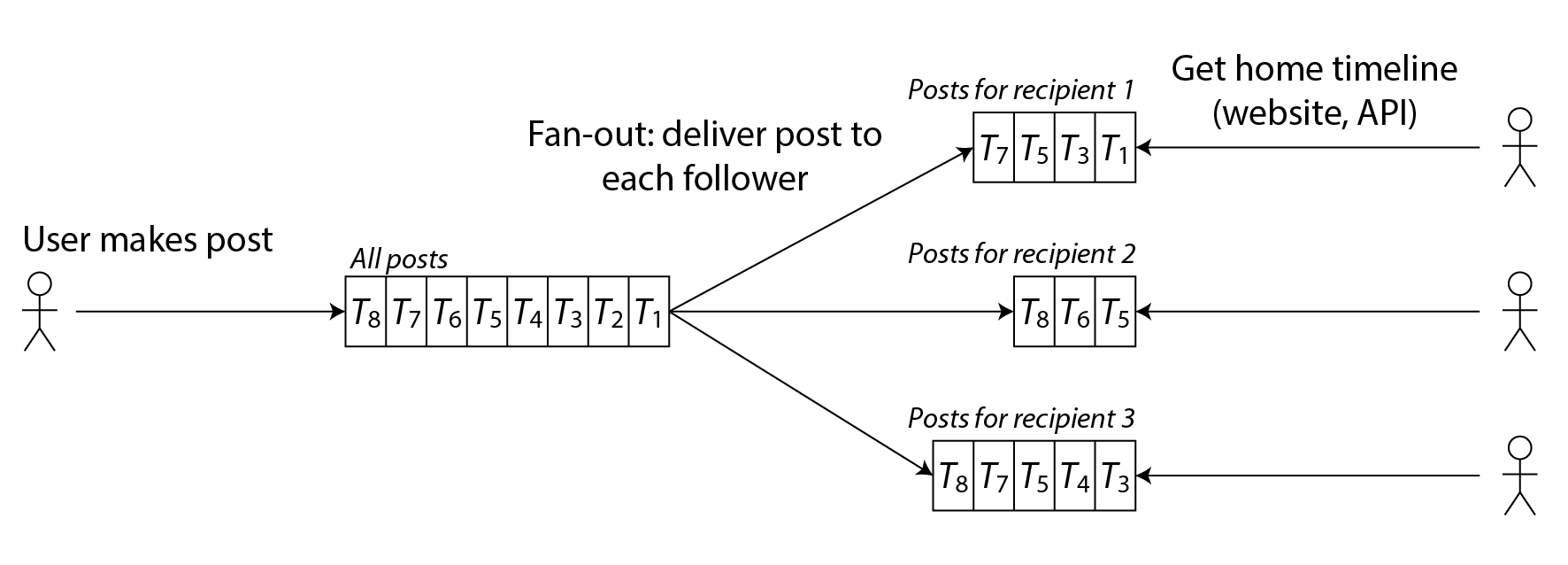

The downside of this approach is that we now need to do more work every time a user makes a post, because the home timelines are derived data that needs to be updated. The process is illustrated in Figure 2-2. When one initial request results in several downstream requests being carried out, we use the term fan-out to describe the factor by which the number of requests increases.

这种方法的缺点在于,现在每次用户发布帖子时我们需要做更多工作,因为主页时间线是需要被更新的衍生数据(derived data)。该过程如图2-2所示。当一个初始请求导致多个下游请求被执行时,我们使用术语扇出(fan-out)来描述请求数量增加的倍数。

图2-2:扇出机制:将新发布的帖子分发给发布者的所有关注者。

At a rate of 5,700 posts posted per second, if the average post reaches 200 followers (i.e., a fan-out factor of 200), we will need to do just over 1 million home timeline writes per second. This is a lot, but it’s still a significant saving compared to the 400 million per-sender post lookups per second that we would otherwise have to do.

以每秒5700条帖子的发布速率计算,如果平均每条帖子触达200名关注者(即扇出系数为200),我们每秒需要执行略超100万次主页时间线写入。这个数字虽然庞大,但相比原本需要执行的每秒4亿次按发帖人查找操作,仍然是显著的节省。

If the rate of posts spikes due to some special event, we don’t have to do the timeline deliveries immediately—we can enqueue them and accept that it will temporarily take a bit longer for posts to show up in followers’ timelines. Even during such load spikes, timelines remain fast to load, since we simply serve them from a cache.

若因特殊事件导致发帖速率激增,我们无需立即完成时间线投递——可以将其加入队列,并暂时接受帖子在关注者时间线中显示稍有延迟的事实。即便在此类负载高峰期间,时间线的加载依然迅速,因为我们直接从缓存提供服务。

This process of precomputing and updating the results of a query is called materialization, and the timeline cache is an example of a materialized view (a concept we will discuss further in later chapters). The materialized view speeds up reads, but in return we have to do more work on write. The cost of writes for most users is modest, but a social network also has to consider some extreme cases:

这种预先计算并更新查询结果的过程称为物化(materialization),而时间线缓存便是物化视图(materialized view)的一个实例(我们将在后续章节进一步讨论此概念)。物化视图能够加速读取操作,但代价是我们需要在写入时执行更多工作。对大多数用户而言,写入成本尚可接受,但社交网络还必须考虑某些极端情况:

更多的写入操作是对比:以前只要向表里插入一条数据即可,现在是要做额外的写入操作

- If a user is following a very large number of accounts, and those accounts post a lot, that user will have a high rate of writes to their materialized timeline. However, in this case it’s unlikely that the user is actually reading all of the posts in their timeline, and therefore it’s okay to simply drop some of their timeline writes and show the user only a sample of the posts from the accounts they’re following [5].

-

如果某个用户关注了数量极多的账号,且这些账号发布频繁,那么该用户的物化时间线将面临极高的写入速率。然而,这种情况下用户实际上不太可能阅读时间线中的所有帖子,因此可以适当舍弃部分时间线写入操作,仅向用户展示其关注账号的帖子样本[5]。

- When a celebrity account with a very large number of followers makes a post, we have to do a large amount of work to insert that post into the home timelines of each of their millions of followers. In this case it’s not okay to drop some of those writes. One way of solving this problem is to handle celebrity posts separately from everyone else’s posts: we can save ourselves the effort of adding them to millions of timelines by storing the celebrity posts separately and merging them with the materialized timeline when it is read. Despite such optimizations, handling celebrities on a social network can require a lot of infrastructure [6].

- 当拥有海量粉丝的名人账号发布内容时,我们需要执行大量工作,将这条内容插入到数百万关注者的主页时间线中。这种情况下,丢弃任何写入操作都是不可接受的。解决此问题的方法之一是将名人发帖与其他人的发帖分开处理:通过将名人发帖单独存储,并在读取物化时间线时将其合并,从而避免将其添加到数百万个时间线的工作量。尽管存在此类优化,社交网络中处理名人发帖仍需要大量基础设施支持6。

-

采访原文:https://www.drdobbs.com/architecture-and-design/interview-with-alan-kay/240003442 ↩

-

Mike Cvet 在 Twitter University 的 YouTube 频道上的技术演讲 How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Fan-In at Twitter。这个频道包含了很多 Twitter 系统设计相关的视频。 ↩

-

Raffi Krikorian. Timelines at Scale. At QCon San Francisco, November 2012. Archived at perma.cc/V9G5-KLYK ↩

-

Twitter. Twitter’s Recommendation Algorithm. blog.twitter.com, March 2023. Archived at perma.cc/L5GT-229T ↩

-

Raffi Krikorian. New Tweets per second record, and how! blog.twitter.com, August 2013. Archived at perma.cc/6JZN-XJYN ↩

-

Samuel Axon. 3% of Twitter’s Servers Dedicated to Justin Bieber. mashable.com, September 2010. Archived at perma.cc/F35N-CGVX ↩